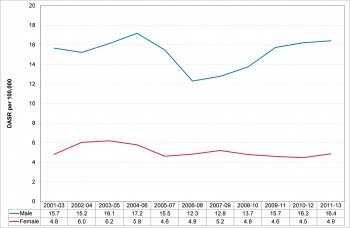

Differences in health between men and women are another aspect of health inequality. While some cancers are gender-specific, gender differences in death rates can be seen in conditions such as coronary heart disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer and suicide (Figure 5.09).

Figure 5.09: Deaths from Suicide or Injury Undetermined by Sex, Direct Age Standardised Rate per 100,000 population (aged 15 and over), 2001-2003 to 2011-13.

Source: Primary Care Mortality Dataset, 2014

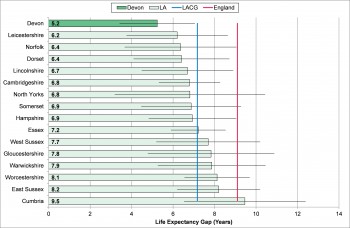

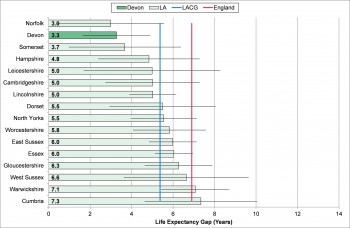

Overall, Devon compares very well with similar local authority areas when considering the size of the gap in life expectancy between areas for both men (Figure 5.10) and women (Figure 5.11).

Figure 5.10: Male slope index of inequality (gap in life expectancy between most and least deprived communities), Devon and Local Authority comparator group, 2011-13.

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework, 2015

Figure 5.11: Female slope index of inequality (gap in life expectancy between most and least deprived communities), Devon and Local Authority comparator group, 2011-13.

Source: Public Health Outcomes Framework, 2015

In England we are fortunate to benefit from a whole range of evidence-based screening programmes, but the proportion of people taking advantage of these programmes is still not as high as we need to ensure that the right people benefit. An example of this is the bowel screening programme. Therefore one action to reduce gender-specific inequality is to ensure that screening programmes are actively targeted at non-attenders, especially those from more deprived areas (because we know the effect of socio-economic deprivation on health-seeking behaviours: when symptoms of heart disease or cancer start to develop, medical help is less likely to be sought).